‘The Warmest Food’: West African Restaurants Emerging In South Carolina’s Lowcountry

BY HANNAH RASKIN

Over the last 10 years or so, a caboose-sized clapboard box in downtown Charleston’s otherwise residential Eastside neighborhood has housed a jerk chicken shop, bagel counter and breakfast burrito joint. But a few weeks after school let out in 2023, up-tempo tunes animated by steel strings and accordions started wafting through the little building’s screened windows.

Maybe passers-by who heard the music from the quadrant of Africa formerly colonized by France guessed that the chef now in charge of the kitchen was working with peanuts and palm oil. Perhaps the lyrics in Arabic and French made them think of slow-cooked lamb nestled in couscous, or fried fish abreast tomato-stained rice.

So far, so good. But if neighbors assumed the chef and her music came straight from Senegal, they were mistaken. Bintou N’Daw was born in Dakar to a family with roots in Saint-Louis, the one-time capital farther up the Atlantic coast, but spent childhood summers with a grandmother in Normandy, France. In her late teens, N’Daw studied baking there for a couple of years, then in 2000 moved to New York City, where she eventually carved out a career as a personal chef for artists.

But first, she worked as an account manager for Putumayo World Music, which is how albums such as “North African Groove” and “Congo to Cuba” entered her music-to-cook-by rotation.

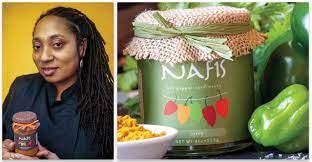

N’Daw’s tiny restaurant, Bintu Atelier, is emblematic of the new wave of West African restaurants emerging in the Lowcountry and along the Gulf Coast, places where the acidic soil and muggy summers mirror West African conditions so closely that the same crops thrive. “Cassava flour, I had to find, but I can go to Joseph Fields Farms and get my okra,” N’Daw said of her buying trips to Black-owned land on Johns Island, 30 minutes from the Charleston peninsula.

Created by longtime culinary professionals with experience in all kinds of kitchens, restaurants such as Bintu Atelier in Charleston, Okàn in Bluffton, S.C., and Dakar NOLA in New Orleans aren’t designed to make guests feel as though they’ve suddenly surfaced on another continent. Instead, they emphasize dishes that draw on native African and French colonial traditions, events that promote community, and open-hearted service.

It’s the format, more than the flavors, that qualifies as a revelation. Bistros passed out of fashion some time ago, as cardiac concerns and qualms over Eurocentrism mounted. But just as a banh mi demonstrates the potential of baguettes, these West African-inspired restaurants show there’s life yet in the French restaurant genre. The homey, welcoming Bintu Atelier could well serve as a model for quality dining as Southern hospitality continues to find its footing in the 21st century.

FRENCH BISTRO MEETS DIASPORIC CUISINE

Money may not buy happiness, but it clearly buys the right to complain. Seated at Okàn’s lively bar, I was astounded by patrons more than once announcing loudly, “I don’t like this,” and pushing aside roasted okra dusted with harissa or a coconut-inflected cocktail.

To be clear, as measured by online reviews and table bookings, Okàn has been a certifiable hit since its July opening, but some wealthy white residents of Bluffton have no compunctions about warning chef Bernard Bennett — a frequent presence on the floor — that his food has “too many flavors.”

“You want boiled potatoes?” Bennett remembers thinking when a guest admonished him to tone down his menu. “I’ve never heard ‘too many flavors.’ But we do have complaints about the sound in the restaurant, and I’ve never been in a quiet restaurant, so that wasn’t expected either.”

To Bennett’s mind, the decibel level is a reflection of diners getting comfortable and going about their lives, just as he intended it.

“We want to be a place where people can have fun and enjoy themselves and not feel stuffy or anything of that nature, and have good food while doing it,” he told me in a phone call after my second visit. “Maybe you want to work on a project at the bar on your laptop.”

It’s a vision remarkably close in detail to the platonic French bistro as conjured by one of its greatest champions. Travel writer Pierre Josse, who served as spokesman for a group that lobbied Unesco to add “traditional French bistro” to its List of Intangible Cultural Heritage, told The Irish Times in 2019 that “the bistro is a ritual, a tradition, the pleasure of being together, of existing.”

He continued, “In a bistro you can be left alone to think, read, write memoirs, poems or love letters.”

That said, Bennett — who was born in Chicago but describes his heritage as “specifically Senegalese” — doesn’t want his audience to disengage from the restaurant’s West African-rooted cooking. Nor does he want them to tune out the history of enslavement embedded in a menu whose influences roam from Portugal to the Dominion Republic to South Carolina and back again. Part of his aim with Okàn is to school customers in the diasporic cuisine’s idioms, so locals can order peanut stew and jollof rice as offhandedly as they might ask for steak frites.

“If I told you I made Italian food, you would have a pretty solid foundation of what I make,” said Bennett, who’s been a chef in Italian, French and New American restaurants. “If I tell you I make African food, you have no clue, or you’re going to go straight to a stereotypical thought like soul food.”

FILLING A VOID

N’Daw has confronted the same confusion about West African cookery, as well as objections lodged against older West African restaurants in the U.S. that she can’t entirely dismiss, given her affection for structure and background in classical technique: “Too oily, or bad service, not open when you think it’s going to be open,” she said.

Yet she never heard those gripes in Charleston, where she relocated during the pandemic in part because of the city’s resemblance to Saint-Louis. In Charleston, where Gullah-Geechee staples such as red rice and stewed shrimp are almost interchangeable with their African antecedents, there simply weren’t any West African restaurants, unless you included the Nigerian woman who sold prepared food out of her home in the next county north.

“There is none?” N’Daw asked her colleagues at Chez Nous, a French restaurant in downtown Charleston where N’Daw worked briefly as a chef.

“None,” they confirmed.

“Nothing?”

When the kitchen on Line Street was offered for rent, N’Daw told her husband that she was going to open Charleston’s first West African restaurant, even if she had to empty their savings account to do it.

Bintu Atelier opened in June as a takeout window. N’Daw instructed her husband, a Fayetteville, N.C., native who gave up his archivist job in New York to help start the restaurant, “I’m going to cook. You’re going to put stuff in bags.” N’Daw was certain of that, just as she was certain that she’d picked a failsafe lineup of opening dishes—ndambe, a black-eyed pea spread; mafe, or peanut stew, and red shrimp with rice—and the right site for her venture: The Eastside reminded her of Bed-Stuy, the intimate Brooklyn neighborhood which she’d long called home.

What she wasn’t sure about was whether she needed to sign up with DoorDash. The food delivery service would keep 30% of her sales, but she worried about running a business without much drive-by traffic. Finally, she registered for an account.

“One day, we tried it, and we had to turn it off,” N’Daw said. The aromas of N’Daw’s cooking, drifting down the street, were a better advertisement for Bintu Atelier than any app listing: She raced to keep up with demand. And once customers received their takeout boxes, they didn’t want to leave. They persuaded her to put patio tables outside her front door so they could stay and eat and talk.

Basically, they’d found their bistro. A place where the food was scratch-made, service was friendly instead of formal, and a chef-owner was keeping an eye on everything, to borrow descriptors from bistro backer Pierre Josse. Of course, this panoramic take on the template was willed into existence by a woman who as a girl would carry baobab to her French grandmother, who craved the Senegalese fruit, and return to Dakar with her Senegalese grandmother’s favorite Dijon mustard.

’THE WARMEST FOOD’

Elaina Ruth, who met N’Daw in March at a small Charleston Wine + Food afterparty organized and attended by Black women chefs, recently had the chance to sit at one of those Ikea patio tables.

“You look up and see it’s just her in the kitchen cooking: Everything that comes out is directly from her hands,” said Ruth, who feasted on fried snapper, crab rice and goat egusi, a ground melon seed stew. “Outside of my grandmother, it’s some of the warmest food I’ve ever had.”

In a city where N’Daw found herself perpetually frustrated by being the only Black woman in restaurant dining rooms — “C’mon! This city is so mixed!” — Bintu Atelier has attracted a diverse clientele. Former Peace Corps volunteers and retirees who’ve had the opportunity to tour an African country still outnumber Black people born in Charleston, but the restaurant’s visited regularly by families who live nearby, women who want to know if palm oil is as healthy as Instagram claims, and kids who want to try fufu like the pounded starch they saw on TikTok.

“I’m happy to see everyone sit together,” N’Daw said. “It’s not about being a Black-owned business, but if you’re Black, you feel safe here. It’s just that simplicity and honesty of feeding and nurturing people.”

Although N’Daw and her restaurant share a given name, N’Daw wanted to clarify that ego didn’t influence her choice. Instead, she was following a family custom in which every eldest daughter, such as herself, is called Bintu.

In other words, Bintu Atelier is designated as the first West African restaurant in the area.

N’Daw’s greatest hope is that it won’t be the last.

Over the last 10 years or so, a caboose-sized clapboard box in downtown Charleston’s otherwise residential Eastside neighborhood has housed a jerk chicken shop, bagel counter and breakfast burrito joint. But a few weeks after school let out in 2023, up-tempo tunes animated by steel strings and accordions started wafting through the little building’s screened windows.

Maybe passers-by who heard the music from the quadrant of Africa formerly colonized by France guessed that the chef now in charge of the kitchen was working with peanuts and palm oil. Perhaps the lyrics in Arabic and French made them think of slow-cooked lamb nestled in couscous, or fried fish abreast tomato-stained rice.

So far, so good. But if neighbors assumed the chef and her music came straight from Senegal, they were mistaken. Bintou N’Daw was born in Dakar to a family with roots in Saint-Louis, the one-time capital farther up the Atlantic coast, but spent childhood summers with a grandmother in Normandy, France. In her late teens, N’Daw studied baking there for a couple of years, then in 2000 moved to New York City, where she eventually carved out a career as a personal chef for artists.

But first, she worked as an account manager for Putumayo World Music, which is how albums such as “North African Groove” and “Congo to Cuba” entered her music-to-cook-by rotation.

N’Daw’s tiny restaurant, Bintu Atelier, is emblematic of the new wave of West African restaurants emerging in the Lowcountry and along the Gulf Coast, places where the acidic soil and muggy summers mirror West African conditions so closely that the same crops thrive. “Cassava flour, I had to find, but I can go to Joseph Fields Farms and get my okra,” N’Daw said of her buying trips to Black-owned land on Johns Island, 30 minutes from the Charleston peninsula.

Created by longtime culinary professionals with experience in all kinds of kitchens, restaurants such as Bintu Atelier in Charleston, Okàn in Bluffton, S.C., and Dakar NOLA in New Orleans aren’t designed to make guests feel as though they’ve suddenly surfaced on another continent. Instead, they emphasize dishes that draw on native African and French colonial traditions, events that promote community, and open-hearted service.

It’s the format, more than the flavors, that qualifies as a revelation. Bistros passed out of fashion some time ago, as cardiac concerns and qualms over Eurocentrism mounted. But just as a banh mi demonstrates the potential of baguettes, these West African-inspired restaurants show there’s life yet in the French restaurant genre. The homey, welcoming Bintu Atelier could well serve as a model for quality dining as Southern hospitality continues to find its footing in the 21st century.

FRENCH BISTRO MEETS DIASPORIC CUISINE

Money may not buy happiness, but it clearly buys the right to complain. Seated at Okàn’s lively bar, I was astounded by patrons more than once announcing loudly, “I don’t like this,” and pushing aside roasted okra dusted with harissa or a coconut-inflected cocktail.

To be clear, as measured by online reviews and table bookings, Okàn has been a certifiable hit since its July opening, but some wealthy white residents of Bluffton have no compunctions about warning chef Bernard Bennett — a frequent presence on the floor — that his food has “too many flavors.”

“You want boiled potatoes?” Bennett remembers thinking when a guest admonished him to tone down his menu. “I’ve never heard ‘too many flavors.’ But we do have complaints about the sound in the restaurant, and I’ve never been in a quiet restaurant, so that wasn’t expected either.”

To Bennett’s mind, the decibel level is a reflection of diners getting comfortable and going about their lives, just as he intended it.

“We want to be a place where people can have fun and enjoy themselves and not feel stuffy or anything of that nature, and have good food while doing it,” he told me in a phone call after my second visit. “Maybe you want to work on a project at the bar on your laptop.”

It’s a vision remarkably close in detail to the platonic French bistro as conjured by one of its greatest champions. Travel writer Pierre Josse, who served as spokesman for a group that lobbied Unesco to add “traditional French bistro” to its List of Intangible Cultural Heritage, told The Irish Times in 2019 that “the bistro is a ritual, a tradition, the pleasure of being together, of existing.”

He continued, “In a bistro you can be left alone to think, read, write memoirs, poems or love letters.”

That said, Bennett — who was born in Chicago but describes his heritage as “specifically Senegalese” — doesn’t want his audience to disengage from the restaurant’s West African-rooted cooking. Nor does he want them to tune out the history of enslavement embedded in a menu whose influences roam from Portugal to the Dominion Republic to South Carolina and back again. Part of his aim with Okàn is to school customers in the diasporic cuisine’s idioms, so locals can order peanut stew and jollof rice as offhandedly as they might ask for steak frites.

“If I told you I made Italian food, you would have a pretty solid foundation of what I make,” said Bennett, who’s been a chef in Italian, French and New American restaurants. “If I tell you I make African food, you have no clue, or you’re going to go straight to a stereotypical thought like soul food.”

FILLING A VOID

N’Daw has confronted the same confusion about West African cookery, as well as objections lodged against older West African restaurants in the U.S. that she can’t entirely dismiss, given her affection for structure and background in classical technique: “Too oily, or bad service, not open when you think it’s going to be open,” she said.

Yet she never heard those gripes in Charleston, where she relocated during the pandemic in part because of the city’s resemblance to Saint-Louis. In Charleston, where Gullah-Geechee staples such as red rice and stewed shrimp are almost interchangeable with their African antecedents, there simply weren’t any West African restaurants, unless you included the Nigerian woman who sold prepared food out of her home in the next county north.

“There is none?” N’Daw asked her colleagues at Chez Nous, a French restaurant in downtown Charleston where N’Daw worked briefly as a chef.

“None,” they confirmed.

“Nothing?”

When the kitchen on Line Street was offered for rent, N’Daw told her husband that she was going to open Charleston’s first West African restaurant, even if she had to empty their savings account to do it.

Bintu Atelier opened in June as a takeout window. N’Daw instructed her husband, a Fayetteville, N.C., native who gave up his archivist job in New York to help start the restaurant, “I’m going to cook. You’re going to put stuff in bags.” N’Daw was certain of that, just as she was certain that she’d picked a failsafe lineup of opening dishes—ndambe, a black-eyed pea spread; mafe, or peanut stew, and red shrimp with rice—and the right site for her venture: The Eastside reminded her of Bed-Stuy, the intimate Brooklyn neighborhood which she’d long called home.

What she wasn’t sure about was whether she needed to sign up with DoorDash. The food delivery service would keep 30% of her sales, but she worried about running a business without much drive-by traffic. Finally, she registered for an account.

“One day, we tried it, and we had to turn it off,” N’Daw said. The aromas of N’Daw’s cooking, drifting down the street, were a better advertisement for Bintu Atelier than any app listing: She raced to keep up with demand. And once customers received their takeout boxes, they didn’t want to leave. They persuaded her to put patio tables outside her front door so they could stay and eat and talk.

Basically, they’d found their bistro. A place where the food was scratch-made, service was friendly instead of formal, and a chef-owner was keeping an eye on everything, to borrow descriptors from bistro backer Pierre Josse. Of course, this panoramic take on the template was willed into existence by a woman who as a girl would carry baobab to her French grandmother, who craved the Senegalese fruit, and return to Dakar with her Senegalese grandmother’s favorite Dijon mustard.

’THE WARMEST FOOD’

Elaina Ruth, who met N’Daw in March at a small Charleston Wine + Food afterparty organized and attended by Black women chefs, recently had the chance to sit at one of those Ikea patio tables.

“You look up and see it’s just her in the kitchen cooking: Everything that comes out is directly from her hands,” said Ruth, who feasted on fried snapper, crab rice and goat egusi, a ground melon seed stew. “Outside of my grandmother, it’s some of the warmest food I’ve ever had.”

In a city where N’Daw found herself perpetually frustrated by being the only Black woman in restaurant dining rooms — “C’mon! This city is so mixed!” — Bintu Atelier has attracted a diverse clientele. Former Peace Corps volunteers and retirees who’ve had the opportunity to tour an African country still outnumber Black people born in Charleston, but the restaurant’s visited regularly by families who live nearby, women who want to know if palm oil is as healthy as Instagram claims, and kids who want to try fufu like the pounded starch they saw on TikTok.

“I’m happy to see everyone sit together,” N’Daw said. “It’s not about being a Black-owned business, but if you’re Black, you feel safe here. It’s just that simplicity and honesty of feeding and nurturing people.”

Although N’Daw and her restaurant share a given name, N’Daw wanted to clarify that ego didn’t influence her choice. Instead, she was following a family custom in which every eldest daughter, such as herself, is called Bintu.

In other words, Bintu Atelier is designated as the first West African restaurant in the area.

N’Daw’s greatest hope is that it won’t be the last.

READ ORIGINAL STORY HERE

Comments