How The World Turns A Blind Eye To African Slavery

Since I was old enough to read about Africa, I have been fascinated by the Tuareg. For more than a thousand years they were the fierce, veiled, camel-riding, sword-wielding warlords of the Sahara until they were ruthlessly conquered in the late nineteenth century by the French Foreign Legion. But when I told my family I longed to journey to the Tuaregs’ Saharan heartland, they would tap their heads signalling that I was crazy.

That chance came after I read that ruthless, nomadic, Tuareg tribes in the small Saharan nation, Niger, ignored world-wide condemnation of their practice of keeping more than 40,000 slaves — women, children, and men — in lifelong bondage. It was known as inherited slavery.

These tragic people were born as slaves, possessions of their masters from the moment they first drew breath until they died. Their owners could do with them what they wanted, even castrate rebellious adult male slaves, and sell them or give them away. They gave slave babies to relatives and friends as gifts.

How was it possible such a slave-owning nation still existed? Why wasn’t the United Nations demanding that Niger stamp out the evil practice? Why did the many nations that honourably brought down the evil apartheid system in South Africa, avert their eyes from a system far worse?

Ten years ago a news story mentioned that the crown prince of a Tuareg kingdom in Niger was bravely fighting to abolish his people’s ancient slave-owning tradition. He was a person I wanted very much to meet.

But first, for a book I was researching, Among the Great Apes, I journeyed to Cameroon. There, I found evidence of the essential connivance of historical African slave traders who sold slaves to white slave traders.

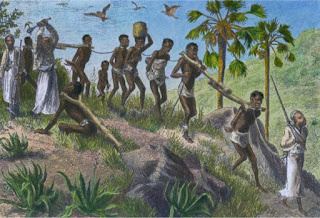

At Bimbia village, its chieftain, Alfred Ejong, confirmed that his ancestors were deeply involved in the slave trade. “Buying slaves and selling them to the white people was good business for our people,” he told me. “In the interior, there were always wars, and victorious kings and chieftains enslaved their captured enemies — men, women, and children. My ancestors went to the rulers to buy slaves and marched them back to Bimbia to sell to whites who came in big ships from across the sea.”

Alfred showed me rusted leg irons and a cutlass, its curved blade flecked with rust: “Our ancestors locked the slaves into chains and marched them here to the coast.” With a grim smile, he brandished the weapon. “Nafonde, a slave master from our village, got this from a white sailor and used it to behead any slave causing trouble. He licked the blood in front of the other slaves to frighten them so none would try to escape. Slave masters who came after Nafonde used the sword the same way.”

A dirt track led down a hill to the Atlantic Ocean. A hundred yards across the dark water was a small, uninhabited island called Niko. “Once the slaves arrived here, our ancestors took them by pirogue out onto the island. The ocean terrified the inland people, and no one dared try to escape. Our ancestors kept them there until the next slave ship arrived from America or Europe.”

Half-way down the slope was a large ship’s cannon partially buried in the damp earth. “An American slave ship captain gave this to my ancestor, the village chief, to use against pirates attacking us, attempting to seize the slaves on the island.”

Was he ashamed of his ancestors’ actions? “We didn’t force people into slavery. My ancestors were the middlemen. The trade existed and if they didn’t do it, others would.”

Slaves being the losers in tribal battles, and their wives and children, was a narrative I heard in Mali and Niger. Inherited slavery was still visibly evident there, as well as in Mauritania, which had an estimated 100,000 inherited slaves, each born to a slave woman. They became the “property” of the slave master at birth and died a slave without even a minute of their lives as a free person.

The flight from Paris to Niamey, Niger’s capital, took five hours. After flying high above the Sahara’s dun-hued sweep, we landed at dawn in a sandstorm. When the jet’s door opened, the 115 °F heat hit me like a furnace’s fiery blast.

Niamey was a sprawl of mud huts pockmarked by a few motley skyscrapers. The narrow streets were carpeted with sand swept in by the wind from the desert that fringed the city. The potholed streets swarmed with people, camels, goats, donkeys, and a few cars. I passed by hundreds of Nigeriens and not one looked overweight. The extreme heat and poverty seemed to pare humans of all fat and any excess flesh.

The Nigeriens moved along the streets with the graceful lope of desert dwellers. The streets reflected the country: a jumble of races, with tall, slim Tuareg men concealing all but their hands, feet, and dark eyes in a swathe of cotton robes and veils. Some flaunted swords buckled to their waists. Fulanis in conical hats and long robes herded donkeys, while the majority Hausa resembled their stocky tribal cousins across the border in Nigeria.

Apart from the occasional Mercedes-Benz, there was little sign of any wealth, reflecting the godforsaken nature of arid Niger. Two-thirds of the country is desert, and its people’s longevity, education and income rank 189th of the 189 countries on the UN’s human development index. More than 60 per cent of its 24 million people lived on less than $1 a day, and most others received not much more.

Idy Baroud, formerly the BBC Niger correspondent, my translator and valued companion on the journey, took me to meet a runaway slave who had bravely escaped life-long captivity. While the country’s leaders played blind to the malady, some slaves, risking a terrible beating, whipping and even castration as punishment, had escaped.

Idy said the police searched for escaped slaves and often dragged them back at gunpoint to their owners. But escapees hid in towns, especially Niamey with its population of 740,000, where they disappeared into its crowded streets and alleyways.

On Niamey’s outskirts, we entered a maze of huts whose mud walls, baked hard as concrete by the fierce sun, led us deep into a settlement that wouldn’t look out of place in the Bible. It housed several thousand people clad in robes, sandals, turbans, and veils. Children garbed in ragged clothing stared wild-eyed at me, while their parents threw me hard glances. Some were escaped slaves and Idy warned that our arrival as strangers could mean trouble.

Timizgida emerged from a mud house carrying an infant and with a four-year-old girl trailing her. She claimed to be about thirty, looked forty, and had a smile that seemed as fresh as her recent good fortune. Like all slaves, she was dark-skinned and said her parents were the slaves of fairer-skinned Tuareg nomads. Sold to her owner, a civil servant, as a baby, she never knew her parents, never even knew their names.

“My master, Abdullah had one wife and four children. I played with his children until I was eight,” she told me in a quiet voice. Then, she was suddenly yanked into the stark reality of captivity. Her fate, from then on, was the same as tens of thousands of other Saharan inherited slaves. She rose before dawn and trudged through the desert to fetch water from the distant well for her owner’s family and his thirsty herds of sheep, camels, and goats. She then toiled all day and late into the night cooking, doing chores and was fed just scraps.

“I was only allowed to rest for two or three days each year, during religious festivals like Eid, and I was never paid. My master didn’t pay his camels and so, he said, why should he pay me and his eight other slaves.” The feisty sparkle in her eyes signalled a rebellious nature, and her owner and family tried to beat it out of her many times with sticks and whips. “Sometimes they thrashed me so hard they drew blood, and the pain lingered for months.”

She was spared one indignity. “My master never had sex with me because he believed it shameful to sleep with slaves like the other masters. I had sex for the first time with a slave boy. My master encouraged me because all my children at the moment of their birth would become his slaves.”

Then, six months earlier, after a severe beating, she escaped, helped by a soldier who pitied her and paid for Timizgida and her two daughters’ bus fares to Niamey. “I shook with fear all the way to Niamey, but every time I looked at my daughters, I knew I must stay strong and never return.”

She smiled as she told me: “I’m still learning what it feels like to be free. Sometimes I wake up and feel very frightened because I think I’m back with my owner but realise I’m now in control of my own destiny.”

Her smile grew wider as she pointed to her daughters, the four-year-old and the infant. “Abdullah will never find me here. My children were also my master’s slaves, but now they’re also free, as will be their children. With freedom I became a human being. It’s the sweetest of feelings.”

History resonates with tales of humans buying and selling each other. In the Bible are many references to slaves, everyday life at that time. The Sahara’s earliest written records of slavery go back to the seventh century, but it existed long before then and sprang largely from warfare with victors enslaving the vanquished. The winners kept slaves to serve their households, work their fields, and to sell them.

In Niger, millions of unfortunates were for centuries yoked together and dragged to North African ports for sale to Europe and Arabia. Millions more in the Niger Basin were taken to West African ports and shipped to the Americas.

Niger was hot as hell during the day. But once the sun set, the temperature plunged so steeply that I breathed easily as I walked to a café near my hotel to meet Moustapha Kadi Oumani, the crown prince of a small, slave-owning kingdom. “Moustapha is fighting to end slavery in Niger,” Idi told me.

He was slim, good-looking, in his late thirties, and clad in a mauve cotton robe and sandals, but no headdress, signalling that he was a modern Tuareg.

Tuareg was an Arab word meaning “abandoned by God”, but Moustapha seemed most assuredly blessed. He was a scion of an ancient tribe that evolved from the Berbers in southern Algeria. The Greek historian Herodotus wrote about the Tuareg in the fifth century BC, noting that they controlled the trans-Saharan trade routes. Their name for themselves was Imazgan, meaning “the free people”.

The café’s open-air tables sheltered under leafy trees, the delight of desert dwellers. There were no women there. Unlike his polygamous father, the king, Moustapha had just one wife. He graduated from universities in Switzerland and Italy, and had returned to his ancient kingdom, more as a twenty-first-century man than as a medieval ruler-in-waiting. He was no wild-eyed rebel, but spoke in a calm, quiet voice that intensified the power of his thoughts on slavery which were regarded as radical, even dangerous, by many in Niger.

“In 1678, my ancestor, Agaba, fought a battle with the enemy – animists – and defeated them. He seized their kingdom, lllela, and enslaved the warriors who fought us, and their families. That meant thousands of people. Their families have been our slaves ever since. Niger’s royal families and nobles have thousands of slaves whom they treat like their camels and goats: no better, no worse. They feed them well, much as they do their livestock. But they keep them in the most degrading condition of life-long slavery.

“The owners can sell their slaves, give them away as gifts, rape the girls, and mistreat them if they are insubordinate. Some have even castrated slaves who refused to obey orders, just as you’d castrate a headstrong stallion.”

“How can slave owners mete out such cruelty,” I asked? “Surely they’re serious breaches of Niger’s legal system?”

“Yes, but my people live far from Niamey in the desert and there is very little law and order there. People do much as they like. They justify slavery as being practised by our people for thousands of years and ask why it should stop now. They say it’s Allah’s will for some to be slave owners and others to be born as their slaves.”

Moustapha’s mother, the queen, before she died, willed her many personal slaves to Moustapha. In a public ceremony in Tahoua, the town nearest his father’s kingdom, Moustapha formally freed them. “Come to Illela with me to meet my father, and slaves and their owners?” he offered. As Idy and I walked back to the hotel, he expressed surprise that Moustapha wanted to take me to his father’s kingdom. “He’s never before escorted any foreigner to Illela.”

when we left next morning, our driver’s face was covered by a white veil, hiding all but his eyes. Moustapha greeted him in Tamashek, their tribe’s ancient language. The driver bowed as he answered.

We faced a journey of 350 miles that would take seven hours. Halfway there, we turned off the road and drove across the desert, a flat, barren plain. We passed a handful of small mud-hut villages. There were no women in sight, but the men, Tuareg, were clad in robes and face veils.

In Niamey they seemed a badge of the man’s ethnic status, but in the desert, they were eminently practical as protection from the wind-blown sand blasting against your face all day.

“All the slaves should be freed immediately,” Moustapha said. “Human beings are resilient, and once they understand they are free, they’ll find their own way. The slaves I freed slipped into normal society without disruption.”

At Tajaye, a small village, we sat outside the mud house of Musa, a veiled Tuareg elder. We sipped syrupy tea served by a wizened, 80-year-old slave woman, Takany, who knelt in front of us. By her side stood her 4-year-old great-grandson, also Musa’s slave.

The child had a frown already etched on his features, his eyes brimmed with sadness, and he was naked, in contrast to several boys and girls his age from Musa’s extended family playing chase around the compound. They were clad in robes, sandals and even jeans, and bubbled with laughter.

During my journey through much of Niger, almost all the little slave children I saw were naked. Like Takany’s great-grandson, they stayed close to their slave relatives, as if for protection, and their features were grim, eyes wary, their step cautious. I never saw any of them smile.

“Slave children in Niger are forced by their owners to go naked at all times until they are five or six years old,” Moustapha explained. “It’s to humiliate them, make them accept they are subhuman. Their masters tell them they’ll be beasts of burden all their life, just like their donkeys, camels, and goats.”

Musa felt no shame in forcing this separation of children into clothed free-born and naked slave. “That’s his destiny,” Musa told me, echoing other slave masters I met. “He was born a bellah (slave) and will die a bellah.”

At mid-afternoon we reached Illela, the capital of Moustapha’s father’s sprawling desert domain. We drove along sandy streets lined with mud-house compounds. About 12,000 people lived there, ruled by his father, Kadi Oumani, the hereditary king. Scores of village chieftains offered him fealty. A quarter of a million people in surrounding villages gave obeisance to Kadi. Moustapha’s survey of Tuareg royalty in Niger found they alone had more than 8,000 inherited slaves. “When a princess marries, she brings slaves as part of her dowry.”

We pulled up outside a mud-wall open-air compound. Inside Kadi Oumani sat on a simple chair, as if it was a throne, with a dozen nobles, all slave-owners, seated cross-legged on the dusty ground around him. Two dozen long-horned cattle, sheep and goats noisily milled about, a deliberate reminder to the Tuareg aristocrats of their nomadic origin.

Kadi was 74 years old and, like his courtiers, wore a robe and a veil left open, revealing his bluff face. Moustapha greeted him and then the crown prince and I walked across the street to an open compound set aside for us.

Wildly pulsating music from a band of drums, horns, and cymbals signalled a ceremony that Tuareg royal protocol demanded. Moustapha motioned for me to sit beside him at the compound’s far end. Then, for the next hour, he greeted powerful nobles who came to pay homage to their king’s first-born son.

It resembled a medieval parade at court to honour the Dauphin’s arrival. Sharp-minded and elegant, Moustapha displayed to the nobles his born-to-be-king nature; his effortless, gracious command of others that came from his family’s generations of unchallenged authority. Each noble, clad in his most splendid robe and turban, entered through a door in the mud front wall. One by one, each strode grandly across the compound and bowed to Moustapha. He remained seated as tradition demanded. He chatted with each for a few minutes, and then the grand departure by one noble was followed by a grand entrance by another lavishly-clad nobleman.

Dinner was lamb grilled over a charcoal fire as a courtier sang for us an ancient, achingly sad, desert tune about love desired, love gained, love lost, and love abandoned. It mingled eerily with the whine of a freshening wind. Above, stars, glinted across the dark sky, attesting to the clean desert air.

Moustapha’s cousin, Oumarou Marafa, a burly, middle-aged nobleman who worked as a secondary school teacher, arrived after we finished the meal. “He’s a slave owner, and not ashamed of it,” Moustapha confided.

Oumarou promptly defended inherited slavery and the practice of taking young slave girls as concubines. “When I was younger, I desired one of my mother’s slaves, a beautiful 12-year-old, and mother gave her to me as a fifth wife,” he told me. “There was no marriage ceremony, she was mine to do with her as I wished.” Islam allowed a maximum of four wives and so the term “fifth wife” was a euphemism for a concubine.

“Did that mean you having sexual intercourse with the girl at that young age?” “Of course. She was ripe for lovemaking.”

A few years later, he tired of her. With Oumarou‘s permission, she went to live with a free man. But Oumarou still considered her his possession. “When I want to sleep with her, she must come to my bed, and she does. Her husband can’t object because he knows I still own her.”

Moustapha confirmed it. “It’s Tuareg custom, and her husband is too scared to object. Oumarou, as a noble, has much power. I want to ban this practice and free all the slaves. My father knows this, but never talks to me about it.”

Oumarou was dismissive of his cousin’s views. “There are many men in Illela with fifth wives,” he said, even though the cost was the equivalent of U.S.$1,000 — three years pay for a labourer. “If you want a fifth wife and have the money, slave owners have young girls for sale here in Illela.”

“Even a twelve-year-old girl?” I asked. “Yes. As young as ten. She’ll be your slave until she dies, and you’ll own any children she has.”

“But you’re a schoolteacher. Surely you wouldn’t sleep with any of your 12-year-old pupils.”

Oumarou clenched his fists and his eyes tightened. “That’s an absurd comparison. They’re children, but the fifth wives are slaves. The bellah don’t think like us, they have no moral sense like us.

“My 12-year-old fifth wife enjoyed sleeping with me. Once I showed her how, she wanted me to make love to her many times every night. I had sexual obligations to my true wives and the slave girl tired me out. That’s why I eventually sent her away.”

Until late into the night, Moustapha and I attempted to convince Oumarou of slavery’s evil nature, trying to change his belief that slaves are a lower sub-species of humans.

“Try and understand the enormous mental pain of a slave seeing their child given away as a present to another slave-owning family,” I asked. “How would you feel if your daughter was given to another family, never to see her again and knowing she was being treated no better than her owner’s camel?”

“You Westerners only understand your way of life and think the rest of the world should follow you.” With that snort he rose, said goodnight to Moustapha and Idy, but ignored me.

Next morning, Moustapha took me to the immense, 300-year-old mud palace where his father was meeting chieftains who had come to honour him or have him adjudicate disputes. Kadi sat on a modest throne from where he daily delivered judgment.

“There are no slaves in Niger,” he told me.

“But I’ve met slaves in your kingdom.”

“You mean the bellah. They’re one of the traditional Tuareg castes. We have royalty, nobles, common people, and bellah.”

“But they’re not free, they’re the possessions of their owners.”

“They are bellah and that is their fate.”

The following day Idy and I drove north to Tahoua. We spent the night in a minus-three-star Hotel Malaria, the prey of giant, buzzing mosquitoes, and departed at 7am. An hour later, turning off the road, we headed into the desert.

There was no one at the first two wells we encountered in that land of meagre rainfall. “The slaves have already watered the herds and gone,” said Fungutan, our Tuareg guide. At the third well, six small slave children were unloading empty goatskin water containers strapped to donkeys. The four younger ones were naked, while the older ones wore ragged robes. When the children saw me arrive, they screamed in terror and buried their heads into the donkeys’ flanks. Trembling in fear, they refused to lift their heads to look at me.

“They’ve never seen a white person before and they’re crying that you’re one of Satan’s demons come from hell,” Fungutan explained. Three women arrived balancing plastic water containers on their heads, having walked barefoot across the burning sand five miles from the tents of their Tuareg owner, Halilou. They covered their faces with cloth and refused to speak to us.

A middle-aged man, also barefoot and clad in a tattered blue robe, appeared walking across the sand. His face clouded when he saw us. “My master said he’ll beat me if I talk to strangers,” he said to Fungutan. He warned the others not to tell their owner about us.

He said they were all slaves of Halilou and his family, living in the Tuaregs’ encampment. Born to one of the family’s slaves, he had toiled for Halilou’s family since he was a little child. He had never received any money, just threadbare clothing, food, and water. Halilou had beaten him many times, but he had never thought of escaping because he wouldn’t know where to go or what to do. “I’ve seen the police catch runaways and bring them back to their masters who then savagely beat them as a warning to the rest of us.”

“Let’s go to Tafan’s tent,” I suggested to Fungutan. Tafan was Halilou’s brother and, Fungutan had told me, one of his slaves, a woman called Asibit, had escaped from him not long before. Fungutan looked worried. “He’s a very violent man. He doesn’t like strangers. He recently cut off the hand of a rival Tuareg.”

Idy persuaded him we should chance it, and for ten minutes the SUV headed across the sand. In the distance I spotted five dark goatskin tents. No one was in sight. All the slaves had gone to work and Tafan’s family were resting in the tents.

A tall, thin man in a robe and Tuareg veil came out to see who was approaching. He went back into the tent and re-emerged gripping a sheathed sword. We stopped the vehicle a few paces from him and got out. “Who are you?” Tafan demanded, glaring at me. “You don’t belong here.” His anger surprised me. In the Arabian desert, the Muslim Bedouin with whom I once spent several weeks welcomed even their worst enemies to their tents in their centuries-old tradition of hospitality. They slaughtered them without mercy in battle, but at their tents offered food and drink to all journeyers in the desert. Fungutan told Tafan I was a writer from a far-off land and was interested in finding out about the bellah.

“My family have owned bellah for generations,” Tafan said. “No one can take them away from us. City people came here and demanded I free them, but I chased them away with my sword. I don’t go to their places and demand they free their goats and donkeys.”

“What about Asibit?” I asked. “What did you say?” he roared.

“Asibit, your slave who escaped.” Tafan yanked out his sword and cut the air. “My sword will tell you all about Asibit,” he snarled. “Get out of here or I’ll cut off your head.”

Fungutan grabbed my shoulder and pushed me back to the vehicle. “He’s a Tuareg like me, and when a Tuareg pulls out his sword, his emotions can overwhelm his common sense, and he can’t control himself. Let’s get out of here.”

Tafan strode towards me looking eager to carry out his threat. I jumped into the SUV and slammed shut the door just before he reached me. His face twisted in anger, he banged the sword’s hilt against the door as we roared away.

Asibit now lived in a town 20 miles across the desert. There, she told me that Tafan’s family had treated her not as a human, but as chattel and a beast of burden. Her eldest daughter, Asibit said, was born after Tafan raped her. When the child turned six, he gave her as a present to his brother, Halilou, a common practice among Niger’s slave owners. Asibit, fearful of a whipping, watched in silence as Halilou took her daughter away.

“From childhood, I toiled from early morning until late at night,” she recalled matter-of-factly. She pounded millet, prepared breakfast for Tafan and his family, and ate the leftovers with the other slaves. While her husband and children herded Tafan’s livestock to the well, she did his household chores and milked his camels.

She had to move his large tent — open-fronted to catch any breeze — four times a day so his family would always be in shade. Now 51, she seemed to bear an extra two decades in her lined and leathery face. “I never received a single coin during the 50 years,” she said. She bore these indignities without complaint, but on a stormy night, she said, she seized the chance to flee, making a dash to the nearest town.

But freedom brought her new difficulties. “Former slaves suffer extreme discrimination in getting a job, government services, or finding marriage partners for their children,” Fungutan told me.

Asibit cannot hope for help from her own government. Lacking the power to confront the chieftains, lacking the space and services in the cities to accommodate a mass release of tens of thousands of slaves, lacking the funds to ease their path back into society, and fearing condemnation by the outside world by that admission of slavery, the government believed it had no choice but to continue to mask the truth and deny that slavery existed in Niger.

Back in Niamey, on my final night in Niger, we talked about how slavery could be eradicated in the country. Idy was pessimistic, believing the chieftains’ power was too strong. But Moustapha vowed to fight on. “We can’t encourage foreign nations to force us into compliance by placing trade sanctions until slavery is ended. We are one of the earth’s poorest nations and that would only impoverish us more and hurt most of all our poor people. That’s half the country.”

“What to do then?” I asked. “Slave owners are not going to free what they regard as their property,” he reasoned, “and while they wield political power, the government will not move against them to end slavery. Pressure must come from outside, especially from the US, France and the UN. Not by sanctions but by political pressure, threatening to turn us into a pariah nation. If these great powers do nothing, then slavery in Niger will never end.”

On the jet back to Paris, I pondered Moustapha’s words. In 1807, Britain banned the slave trade throughout its vast empire, and in 1865 the United States abolished slavery and freed all slaves under the Thirteenth Amendment. But more than 100,000 inherited slaves in Niger, Mauritania, and other Saharan countries suffer as the chattels of their often brutal masters.

“How much longer will the outside world ignore their cruel fate?” Moustapha had said back at Illela. “How much longer must they wait to be free?”

Postscript

Extracts from the U.S. State Department webpage: “2022 Trafficking in Persons Report: Niger”

In the Tahoua region, influential chiefs facilitate the transfer of girls from impoverished families to men as “fifth wives” for financial or political gain. This practice — known as wahaya — results in some community members exploiting girls as young as nine in forced labor and sexual servitude; wahaya children are then born into slave castes, perpetuating the cycle of slavery.

The government reported minimal law enforcement action to address hereditary slavery practices, including the enslavement of children. [It] did not report law enforcement statistics on investigations, prosecutions, or convictions of traffickers exploiting victims in hereditary slavery, [or] traditional chiefs who perpetuated hereditary slavery practices.

Hereditary and caste-based slavery practices perpetuated by politically influential tribal leaders continued in 2020. Some Arab, Zjerma, and Tuareg ethnic groups propagate traditional forms of caste-based servitude in the Tillaberi and Tahoua regions, as well as along the border with Nigeria.

READ ORIGINAL ARTICLE HERE

Comments