Shame On US Scholars, Writers For Intellectual Imperialism Against Haitians

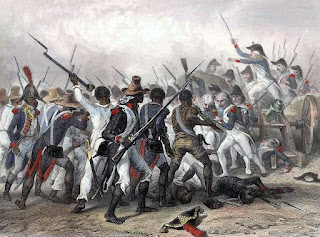

The Haitian Revolution: Attack and take of the Crête-à-Pierrot (March 24, 1802) Image: Auguste Raffet

American academia produces some of the most arrogant and selfish academics and thinkers in the world. Because most American scholars and historians write and publish in the English language, works published by Haitian, Caribbean, African or other Black writers — who write in French or Spanish — are deemed worthy of intellectual value only when written in English. These American scholars do not assess the quality of scholarship or good research, only their own ability to process the information in English.

This attitude is nothing but intellectual imperialism at play. This pernicious perspective is rooted in the politics of the American Empire as a means to undermine the intellectual and literary productions of writers and historians in the Global South or developing world. Haiti, because of its complex history with the United States and the West, as well as with American and Western academics and writers, is a primary victim of this intellectual climate.

Over the years, I’ve observed American academics and writers not bother to cite Haitian writers who had been writing about an issue for decades.

I mean c’mon, good people: How can you pretend that nobody in Haiti wrote about Haitian national history or Haitian intellectual history from the 18th to the 20th century? Just because you write in English for an American audience does not mean you must disengage with a body of scholarship produced in a different language. It is intellectual dishonesty not to give credit or acknowledge intellectual predecessors.

American scholars: Stop ignoring writers publishing intellectual productions in their native language. Shame on you for not giving Haitian studies legitimacy because it is not in English. Shame for thinking that only you can humanize the Haitian people because you write in English about Haiti and the Haitian experience. I’m not referring to Haitian-born writers or those of Haitian descent who write or produce in English. This is not my point here.

Unfortunately, in American academia, producing academic works in English does come with academic entitlement or pedigree. It brings a great deal of academic privileges and reputation because the English language has now become more connected with the politics and expansion of the United States as the world’s most powerful country and empire today.

Fluency in English does not denote intelligence

Nonetheless, fluency in English does not make one naturally more intelligent. I know this is a popular attitude among Americans, even among some American academics, that speaking or writing in English is connected with high civilization or culture, intelligence, and fame. Such an attitude needs to go. Let’s stop this colonial practice, as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o urges us to do in “Decolonizing the Mind.”

After all, no one else expects American academics to be fluent in French, Spanish, Kreyòl, Swahili, Swahili, Yoruba, Igbo, Fula, or any other language than your native tongue: English. The least you can do, if you are going to work or specialize in a non-English speaking country as a scholar or academic specialist, you should try to “read in translation” or even to “cite in translation.” Or you can seek the help of an expert.

Interestingly, American academics do not express this same attitude toward French, German, or English writers or historians when writing about the history and experience of western countries.

How to move forward and change this bad academic practice in America’s intellectual or academic landscape? First, realize that Haitian writers and historians have written prolifically and produced good works about some key issues in Haitian national history. To name a few: The Haitian Revolution, Haiti’s colonial history/Slavery and colonization in Haiti, France’s economic exploitation of Haiti, American military occupation and invasion in Haiti, the rise of Haitian radicalism and Marxism in the 20th century, the rise of Feminist movement in Haiti, the Duvalier regime, Haitian anthropology and ethnology, and the politics of NGOS in Haiti.

For each historical period, I can list 30 to 45 influential writers and thinkers to get acquainted with, especially those published in the French. Many more thinkers are on my list alone.

Remember, scholarship is a team effort

I wrote this post in response to a series of The Ransom articles published in the New York Times. For academia, the main takeaway here is that academic scholarship is a team effort that engages the labor of other scholars, for which I am thankful. In other words, no one works in isolation, and no one can claim intellectual monopoly when it comes to academic studies, research, and epistemology. Yet, we must not ignore those who are writing on the margins and work predominantly from the context of a developing country in the Global South. Their work matters! Their ideas are worth citing — in English! Their contribution is worth acknowledging in public.

We have a Haitian canon, built on existing traditions — intellectual practices, ways of thinking, perceiving and interpreting the Haitian world and other worlds in Haitian history — that encompass various worldviews, fields of study and areas in the human and Haitian experience. Similarly, since Haiti’s birth in 1804, the country has seen numerous movements that have shaped the human experience in Haiti. Haitian writers and historians have documented their own histories and stories, experiences and living conditions, and such literary receipts could be traced to the country’s first piece of writing: Haiti’s Declaration of Independence on January 1, 1804.

Clearly, Haitian writers have not been silenced about the Haitian experience in the world. The world, America in particular, should not erase that tradition of Haitian scholarship either.

Celucien L. Joseph, PhD, is Associate Professor of English at Indian River State College.

Comments